POINTS OF VIEW

By Phyllis Tuchman

Isca Greenfield-Sanders’s figured landscapes¹ transport viewers to light-dappled lakes, mountain trails, rustic sites where wild flowers bloom, and ocean shores bounded by sandy beaches and sunny skies. These are well-trodden places that people like to visit. Often, they appear to be startingly familiar. You might feel that you have already been there—or to somewhere very similar. There’s her noteworthy palette to consider, too. It’s unobtrusive. Though you immediately notice how this third-generation artist² occasionally swaddles her scenic vistas in pinks or blues, you probably remain unaware that she also practices restraint. She doesn’t overload her canvases with lots of different colors.

As it is, Greenfield-Sanders upends our notions of how landscape artists proceed. She is not a plein air painter. She does not sketch, let alone create watercolors, in front of her motifs. Indeed, she does not even visit the places she lovingly portrays. Instead, Greenfield-Sanders makes all sorts of decisions as she creates her works from scratch. In some ways, what she does can be compared to the skill set of an author who writes nonfiction novels or the director of a movie that features real-life characters.

Over the course of many years, Greenfield-Sanders has developed a highly original manner for executing her compelling landscapes. It involves several unusual steps. “In the early years,” she recently said to me, “I wasn’t thinking about a format.” For starters, she collects vintage 35mm slides from the 1950s and ’60s³. Many come from garage sales; others are purchased from dealers who stock old Kodak color slides. She has discovered that amateur photographers consistently take pictures that have much in common. That is, the friends and relatives who pose for them change, but the settings are more alike than you might suppose4. One afternoon in her studio, which is not far from where she was raised in lower Manhattan, she told me that she finds “the randomness very appealing.”

“Almost every lot,” she added, “has something special.”

Once Greenfield-Sanders chooses an image that she might eventually paint in oil on a substantially sized canvas, she makes at least one watercolor, and sometimes more, of the subject5. She does not necessarily respond to the whole scene. Occasionally, she might duplicate only a section of a photograph. By the time she is done, she may have moved a few figures or even some trees from their original locations. She will even obliterate the sky.

After Greenfield-Sanders has completed the watercolors, she will make 17-inch-by-17-inch oil paintings based on them. These become guideposts for the larger canvases. At this stage, she has determined many aspects of what will appear in the final works, including their colors, overall composition, and how she might deviate further from the original image6.

Like actors who ad lib from a script, Greenfield-Sanders can be quite improvisational. Unlike other landscape artists, she reminded me last March, “I’ve never been to these places.” Or, as she forthrightly explained, “I’m not aiming at realism.”

Greenfield-Sanders’s latest paintings of beaches, including Silver Beach (Blue), Pink Wave (Detail), Blue Wave (Detail), Aerial Beach, and Bathers, illuminate the variety of approaches that inform her art. She carefully adjusts the vantage points for viewers. We do not consistently look straight ahead. Unsurprisingly, given its title, Aerial Beach presents a bird’s eye view of the scene below. From a great height, we look down on the bathers and the ocean. (If the figures were not there, we might not realize how high up we are made to feel.) Then, there are times when Greenfield-Sanders puts us so close to the ocean, as in Blue Wave (Detail) or Pink Wave (Detail), that we can practically feel the tumultuous, roaring water splashing against our faces.

“I love painting water,” she said not long ago. “If there’s one thing I think my technique is suited to, it is water. The layering that I use creates paintings with depth and vibrancy.”7

She also takes into account how she situates her bathers. They don’t face us. They are not looking at the camera and saying, “Cheese.” With their backs turned toward us, we’re gazing at what they are regarding. There is a term for these beachcombers: They are “Rückenfiguren,” which we are used to seeing in, say, paintings by Caspar David Friedrich, the German Romantic artist. There are not a lot of details to distract us. You won’t find product placements, as you would in a photorealist picture from the 1970s. Nor, for that matter, are we overly conscious of the types of bathing suits these figures wear. This allows us to identify even more with the scenes Greenfield-Sanders paints.

And then, there are the colors she applies to her canvases. When depicting water, sand, and sky, Greenfield-Sanders often uses lots of blues or pinks. Recently, she executed two versions of Silver Beach, one in blue and one in pink. Because these canvases are so similar, you can see just how thoroughly Greenfield-Sanders has transformed photographs taken by other people into her own independent paintings.

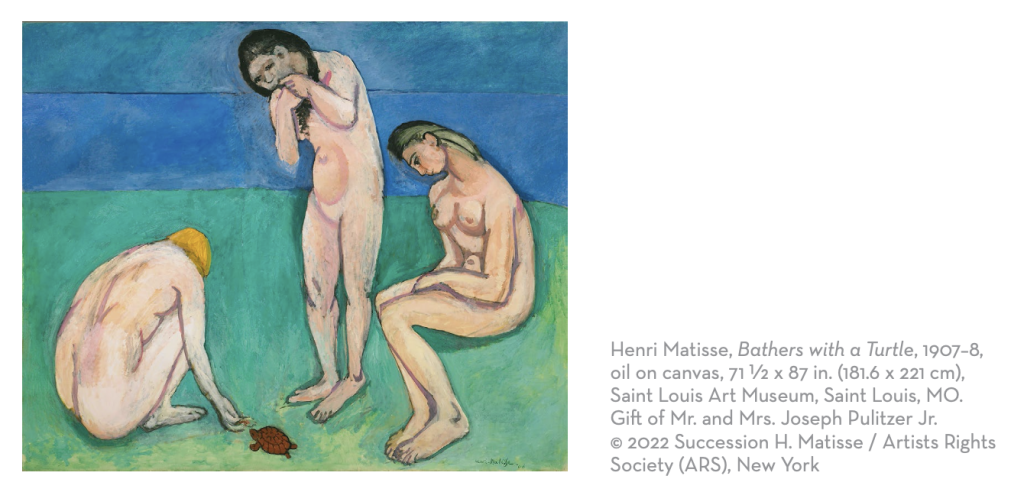

The two versions of Silver Beach are comprised of three stacked, broad bands that portray sand, ocean, sky. These substantial stripes are so forceful that it is difficult to believe the canvases on which they appear are squares and not horizontals. The broad bands also call to mind a pair of predecessors painted decades apart: Henri Matisse’s Bathers with a Turtle and Brice Marden’s Grove Group. This connection with earlier banded works is yet one more way Greenfield-Sanders reminds us that she is making a painting, not duplicating a photograph. As she told me a few months ago, “None of the colors are natural. I use a fairly tight set of colors that work with one another.”

Many of us who live on the East Coast have been to the seashore. We’ve felt the scorching sun beating down on us. We’ve walked on the hot sand. We’ve sat on towels or lounged on chairs under umbrellas looking off into the distance. We’ve ventured into the saltwater to jump the waves or body surf. When we’ve left, we’ve had to figure out how to clean off the wet sand clinging to our feet. But this is not what Greenfield-Sanders is depicting. She’s creating general—not generic—impressions. She’s providing us with memories that we actually have not experienced on our own.

Mountain View and Red Wood represent the more rugged, hearty side of Mother Nature. We find green trees and billowing white clouds in this sort of terrain. Where beaches suggest summertime leisure and people bobbing in the water or relaxing on the sandy shoreline, mountains call to mind adventure and more individual pursuits. One type of scene tends to be low-lying while the other can be dominated by gigantic trees. Indeed, the redwood in the painting of the same title is so tall that it is, again, hard to believe that the canvas is a square and not, in this instance, a vertical. Instead of looking down, we glance up.

With Field Flowers and Queen Anne’s Lace, Greenfield-Sanders truly rounds out the diverse ways we experience her art. The wildflowers she depicts grow so densely and appear to be so close to us that we feel as if we are practically confronting a jungle. By filling her canvases with these growths, we occupy what’s called a worm’s eye view. These paintings, which feature so many plants and flowers, also are the most animated. Do we hear birds chirping? No, it is more like insects issuing a symphony of sounds. And, as we imagine their cacophonous tones, we realize just what a rich sensory experience Isca Greenfield-Sanders offers viewers of her art. This is landscape painting refreshed and practiced with understated originality.

___

Phyllis Tuchman writes for artnews.com, Artforum, and the New York Times. In summer 2018 she curated the exhibition Ellsworth Kelly in the Hamptons for Guild Hall, East Hampton, and lectured on Helen Frankenthaler at the Provincetown Art Association. She is currently working on This Is the Land: The Life and Times of Robert Smithson.

___

Endnotes

1. This is the term that Greenfield-Sanders uses when referring to her own paintings; uncited quotes are from a conversation the two of us had this past March.

2. Greenfield-Sanders is the granddaughter of Joop Sanders, an abstract painter, and the daughter of Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, a filmmaker and portrait photographer. Greenfield-Sanders told me she has always painted landscapes. In high school, she was drawing with charcoal and pen as well as executing watercolors. At Brown University, she majored in both mathematics and art. She would take her academic classes in the morning and study at the Rhode Island School of Design in the afternoon.

3. She estimates that she has looked at thousands and thousands of slides.

4. A talk delivered at the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, March 2020; available on Vimeo. According to Greenfield-Sanders, “I see a lot of images of Old Faithful, the geyser; I see days at the beach, backyard picnics, monuments, vistas, and things I’m not interested in like birthday cakes.”

5. A conversation recorded at the Haunch of Venison gallery in London, November 2012; available on YouTube. About working with watercolor, computer printouts, and paint, Greenfield-Sanders has said, “I try to highlight what I think are the best qualities of each medium. Oil has this vibrant, luminous color, especially when used transparently, which is what I do.”

6. Ibid. “Working with someone’s inherited images frees me from the subject,” Greenfield-Sanders has said. “This gives me the opportunity to build an image that is layered with photographs, watercolors, and oil paints.”

7. Op. cit., Institute of Fine Arts, New York University